Woman on street (2018 Third Prize)

2008 Third Prize Winner

Woman on Street

Nandi Dill

Photo Essay

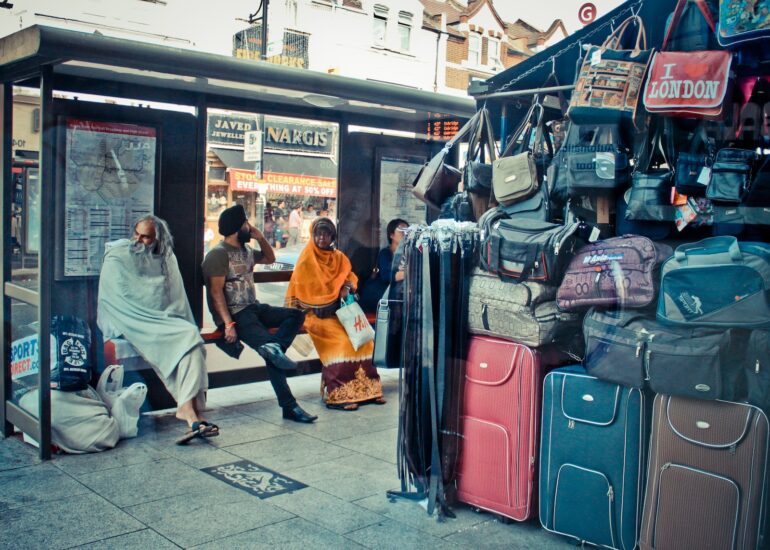

She stands alone, buildings towering above. The city, engulfed in light, moves beneath and around her. Her body, in what seems a momentary stance is mostly covered. Only her face and bare hands show beneath the losely draped fabric.

Read as an everyday street scene, this image may not arouse suspicion or even much close attention. But what appears as deceivingly simple may in fact be a product of those things that take place behind the scenes and beyond the camera’s immediate gaze. The work of visual sociologists and skilled photographers encourages us as viewers to take into account both what we can and can’t see in a picture—the slight lift of her leg (Is she about to leave? Are people waiting for her?) or the bus zooming by (Did she just miss her trip away from there or is she comfortably plotting her next move?). Also, does her attire suggest that in her movement, or even stillness, that she’s bound by certain beliefs or principles? Or in her presence against the grit of the city, the traditional and modern neatly juxtaposed, does she challenge that association?

While the image itself does not provide any simple answers, it reasserts many of the complicated features of our globalized existence. As beautifully illustrated in Rachel’s photographs, globalization alters the relationship between the individual and society: basic goods travel miles to reach our homes and ideas flow across boundaries at unprecedented rates. We could say, then, that globalization is partly responsible for the woman’s presence on this New York City street corner.

But we must also consider that in enabling the movement of people, ideas and cultures and in placing this woman on a busy street or putting Pepsi advertisements along a Guatemalan lakefront, globalization gradually allows for places to take on similar visual scripts. It draws the distant closer and in doing so makes Rachel’s image of the Cuban boy and his bicycle not so foreign: although the caption tells us its Cuba, the brick setting and the attention he gives to his video game does not distinguish him from many other boys around the world.

So while certain symbols in this image tell the viewer that this woman is in New York City and not in Paris, Cairo or even Barcelona, a cursory glance would not tell the entire story. Upon first look she appears to stand alone. But the lens of globalization tells us she’s not. She’s inevitably linked to women moving about the busy streets of the world, taking a step in her same shoes and ultimately reshaping the society within which they all stand.

I conducted ethnographic research with tech developers who design digital technologies applied to farming. In their work, drones, sensors, and autopilot tractors are projected to make planting, fertilizing and harvesting possible through algorithmic devices. In this new scenario, workers become responsible for fixing and riding tractors, and dealing with touchscreens that commanded the machinery.

When I encountered people working on the land, I was puzzled. Why was human labor missing from the images my interlocutors showed me? Why drones never photograph workers’ bodies? Why is satellite imagery used to account for farm productivity? My interlocutors would say that images produced from above produce data that improves decision-making. I then decided to use my phone’s lens to think through a different perspective. The farmworkers were more than a reminiscence of the past.

Six men stood on the edges of a platform carrying hundreds of pounds of sugarcane. While the platform moved slowly, each man grabbed three stalks at a time and threw them on a furrow. Behind them, six women walked inside the trenches, using a long machete to place the stalks in the right position and cut them into pieces. This technique is used to prevent the stalks from bending when sprouting, guaranteeing the health of the newborn plants.

The work was arduous. With no shelter from the sun, no facial protection against the dust raised by the trucks, the women lift the heavy machetes with one arm, while the other leaned on their back, to avoid pain. “Women are more delicate”, one of them said, and a male tractor driver added: “Men don’t care if cane overlaps. Women pay more attention to detail, they are more careful”.

Feminist scholars have shed light on multiple situations in which emotional labor and exploitation function together. This photograph is, then, a reminder that contradictions coexist. The women’s work with machetes is both gruesome and meticulous. The heavy metal boots prevent toe cutting, while they pick colored scarves matching with the t-shirts to avoid neck sunburn. The women’s role in that farm was determined by a larger patriarchal system that put them in the place of caregivers, wearing their bodies down. And yet, like Brazilian writers Helena Silvestre and Carolina Maria de Jesus state, wherever there is life, there is a drive to live.

Photographing these women and their techniques to style and protect their bodies, therefore, does more than revealing something that might be missing in the lenses of drones and satellites. Photographing human labor, especially women’s, in contexts where people are supposedly inexistent, is a way to account for the lives obfuscated by the contemporary narratives of modernization, progress and digitization of industrial agriculture.

Commentary on Rachel Tanur's Works: Cuban Boy with Bike and Game

What touches me most about this image is not the bike, which comfortably rests near this young boy, and is not the game which he devotes the majority of his present attention to. But it’s his white tennis shoes neatly tucked below the cuffs of his pants that draw my eyes in. We can imagine that these same shoes were at once one with the pedals of the bike, propelling him down a bumpy Cuban street and finally propping him up when he and the bike came to a complete stop.

Like the bike and the game, the shoes speak of movement – the movement of people, of ideas and of cultures. Globalization makes this possible. The picture does not tell us how far he had to travel to find this comfortable nook to entertain himself. And we can only imagine how far these precious items had to go to find him in Cuba. Nonetheless, this photograph is a powerful reminder of the reach of globalization and its ability to facilitate contact with distant and diverse people and objects. One wonders whether the tides of globalization will make it so that this image and the boy’s shoes no longer touch us, but both fold into well-known views of our modern world.

Recently in Portfolio