Good Night, God Bless (2025 Second Prize)

2025 Second prize winner

Good Night, God Bless (2025 Second Prize)

Photo Essay

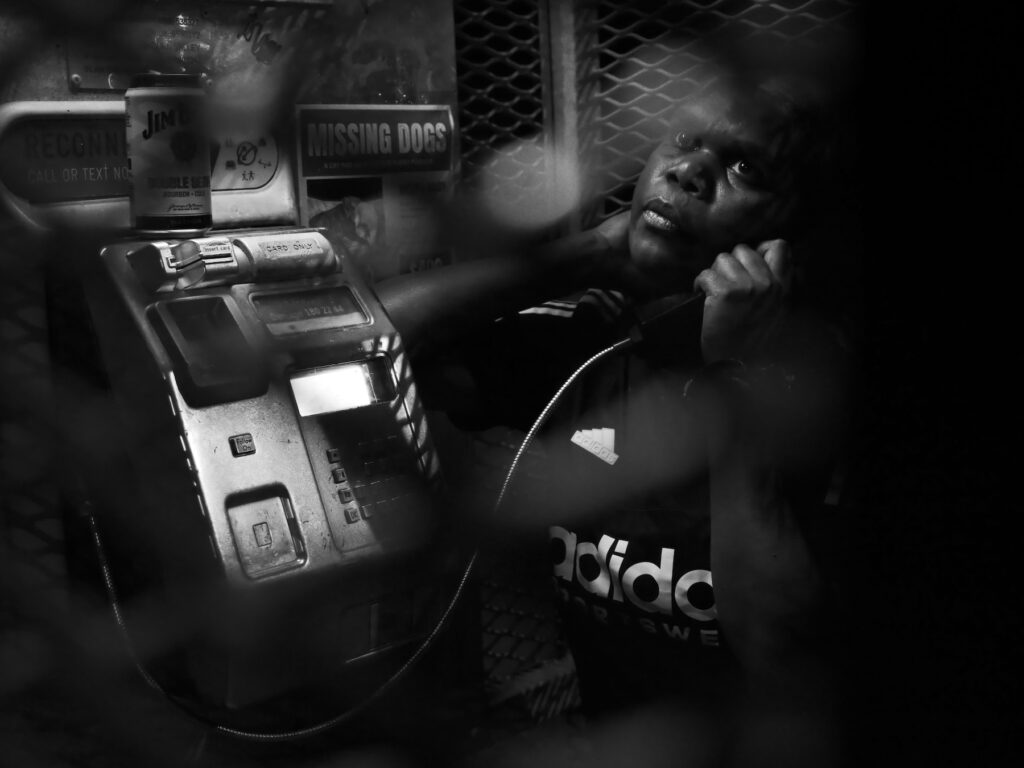

In this photograph, Marie, a 26-year-old Luritja woman, uses a payphone, late at night, to call her husband in prison. Peter has been incarcerated for two weeks for breaching a domestic violence order, unique to the Northern Territory, which states that couples can live together and be in one another’s company except when they are intoxicated. Any violation carries a mandatory prison sentence. They excitedly discuss her plans to visit him the following day. Marie and Peter’s story has become strikingly familiar during my three years of ethnographic fieldwork in Alice Springs, a small town in central Australia, where I reconstruct the logics of settler-colonial hyperincarceration and effects of penal power on people’s lives. While the dominant leitmotif of American mass incarceration is the “War on Drugs,” amongst Aboriginal people domestic violence is the primary engine of penal growth.

Through fieldwork, I have entered a closed network of Luritja families—an Aboriginal Australian cultural group whose homelands lie West of Alice Springs. In contrast to street-photographers who engage fleetingly with their subjects, visual ethnographers build intimate relationships which allow them to get closer to the totality of the interaction, relink the image with its socio-structural context, and capture the messiness of real life. Out of focus and hidden in the left-of-frame is a can of Jim Beam. To make this call, Marie has snuck away from the house where she drinks with her boyfriend (who happens to be her husband’s cousin-brother). Far from grieving Peter’s absence, she capitalizes on his time in prison to embark on her own affairs, allowing her to recapture lost honor associated with her husband’s betrayals, telling me “it’s my turn now.” Marie’s pursuit of autonomy, freedom, and hedonistic pleasure challenges the orientalist tropes upon which the settler colonial project and contemporary penal policy are founded. These representations, powerfully deconstructed by postcolonial scholars (Said 1979; Spivak 1998), portray Indigenous women as hopeless victims who must be saved by the civilizing power of the colonial state. By documenting and contextualizing the ambivalence of Marie’s life, this project can further a project of decolonization by establishing Aboriginal people as autonomous agents over their own lives.

However, while visual ethnography gets us closer to understanding the complexity of participant’s lives, it is important to acknowledge that it is still a fictionalized account framed by the unequal relationship of the photographer and photographed. This is particularly sharp in a colonial context where I am a non-Luritja, white woman photographing Luritja people. Rather than denying this perspective, this photograph, like the broader series, interweaves politics into aesthetics and shoots through, rather than against, the white gaze. Each photograph marries two seemingly contradictory principles of intimacy and observation. It gets close to the physical and psychic emotion of their lives. In this photograph, the Rembrandt lighting perfectly spotlights her face, demanding the viewer engage immediately with the intensity of her eyes. At the same time, however, it uses the phone-box’s wire mesh to establish the continued distance between Eliza and myself, and demonstrates the limits of intimacy and solitary engagement.

Commentary on Rachel Tanur’s Works: Guatemalan Pottery

Sociologists and photographers are kindred spirits, bound by a shared paradox. Each harbor a transgressive potential because they enter otherwise closed communities and violate class and cultural boundaries. Yet they can act as conduits for power because they carry messages through these very divides. I chose this photograph from Rachel Tanur’s collection not only because it provides a portrait of colonial femininity that mirrors my own image, but because it raises two questions crucial to the double-sided ethics of photography and sociology: ambiguity and positionality.

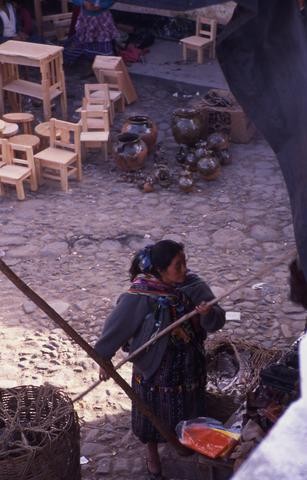

Rachel Tanur’s photograph “Guatemalan Pottery” is filled with ambiguity. It captures a young woman, likely Indigenous, holding a stick, which is placed inside a woven basket. The title provides the most significant contextual clue, but still who she is and what she is doing is left vague. Is she at home or work? Is she making the basket or using it? In doing so, the image deliberately creates space for interpretation, the projection of meanings and extrapolation out to large-scale forces. This interpretation, however, is in the eye of the beholder, and subject to one’s cultural values, ideologies and position within a web of power. Drawing on my own experience studying Indigenous women living under colonial domination, I might be tempted to read her as a victim of colonial violence, confined to hidden, shadowy spaces and forced to engage in denigrated, gendered labor; I could alternatively romanticize her, as a heroic vestige of artisan production in an era of mass-marketed commodities. Each reading, however, risks presenting her as an exotic and dehistoricized other and can fuel a voyeuristic pornography of suffering that obscures the fuller context of what is occurring outside of the frame (Said 1977). The violence of the image therefore comes from its lack of context, which can essentialize difference and obscure causal forces (Sontag 1977; Bourgois & Schonberg 2009).

What I appreciate about this photograph, however, is that it does not deny this voyeurism, but embraces it, because its composition immediately thrusts the question of perspective onto the viewer. It departs from the majority of images in Tanur’s collection, which oscillate between establishing landscapes or intimate portraits in two key ways. Whereas in many photographs, the subject looks directly at camera, this woman seems unaware of the camera, which allows Tanur to capture her subject authentically undertaking the mundane, everyday activities that shapes her life. More significantly, however, Rachel towers above the woman and almost voyeuristically surveys her subject. Like my photograph, Rachel frames the image through an artifact– perhaps a balcony or umbrella, which adds to the voyeuristic gaze and sensation that someone is watching. This angle produces a distorted subjectivity, which obscures her face and the relationship to the basket, increasing the ambiguity of the event. In doing so, she immediately establishes the point of view of the photographer, conveys her objectifying distance and thrusts upon us the power dynamics between the woman and Rachel as a foreign female photographer. This perspective resonates with my own project.

Recently in Portfolio